Welcome as always to ‘Final Frontier Friday‘! The torch has been passed to ‘The Next Generation’, and now it’s time for that generation to spread its wings! This week, we’re continuing our countdown to the premiere of ‘Star Trek: Discovery‘. This week we’re taking a look at the two-hour debut of ‘Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’. So settle in as we begin our look at ‘Emissary’.

Despite a shaky start, ‘Star Trek: The Next Generation’ had found its footing by 1991. With the new series thriving, Brandon Tartikoff (then President of Paramount) felt it was time to launch a third ‘Star Trek’ series. And so that summer, Tartikoff approached Rick Berman (who had increasingly been assuming stewardship of ‘Star Trek’ in the face of Gene Roddenberry’s declining health) about developing a new series. ‘Star Trek’ has always had the influence of the western genre written into its DNA, and at Tartikoff’s suggestion, ‘Deep Space Nine’ would draw inspiration from the scenario of a father and son setting up shop in a frontier town. If ‘Star Trek’ was ‘Wagon Train’, then ‘Deep Space Nine’ would be ‘Gunsmoke’.

This frontier town premise had the benefit of distinguishing the new show from ‘The Next Generation, with which its run would overlap. While ‘The Next Generation’ and its predecessor both followed formats that effectively mandated that their crews would be somewhere new and different every week, the new show would by necessity place a greater importance on familiar settings and characters. The show’s premise similarly helped to sketch out the characters at this stage, providing a template that would be reflected in the final product. Indeed, longtime writer Robert Hewitt Wolfe has noted that most of the characters map broadly onto a variety of western archetypes, including the mayor (Sisko), the sheriff (Odo), the scheming bartender (Quark), the common man (O’Brien), and the Native American (Kira).

As I’ve alluded to, the show’s premise dictated that it be set in one place, as opposed to an ever-mobile starship. In the earliest stages of development, this fixed location was a literal frontier town located on a colony world. This was eventually rejected in favor of a space station, partly because of the demands that a planet-based show would face in the form of location shooting, but also because it was felt that ‘Star Trek’ fans preferred space-based stories.

In either case, this opened the doors to an entire storytelling style that ‘Star Trek’ had only occasionally dipped its toe into at that point: one driven by consequences. As Wolfe phrased it, “If ‘Next Generation’ and the original series were about going out there and discovering new things about other races, ‘Deep Space Nine’ is about staying in one place and discovering new things about ourselves.” Executive Producer Michael Piller, on the other hand, likened the contrast to the difference between a marriage and a one night stand. But however one prefers to describe it, the point is that this approach not only set ‘Deep Space Nine’ apart from ‘The Next Generation but did so in such a way as to give the show an identity all its own.

But of course “different” doesn’t always mean “good,” does it? While we all know where ‘Deep Space Nine’ would go over its seven-year run, none of that really has any bearing on the quality of the pilot itself. So was it a strong start or something more akin to the early stumbling of ‘The Next Generation’? Read on…

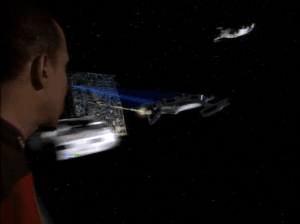

We open in the midst of the Battle of Wolf 359 (the aftermath of which was glimpsed in the classic two parter ‘The Best of Both Worlds’). Aboard the Saratoga, things quickly go from bad to worse. The captain is killed and first officer Benjamin Sisko gives the order to abandon ship as the Borg overwhelm their defenses. As the evacuation begins, Sisko runs to his quarters. There, he finds his young son Jake (who is rushed to a shuttle) and his wife Jennifer, who has been killed and partially buried under debris. Beside himself with grief, Sisko has to literally be dragged to the evacuation shuttle. Safely aboard the shuttle, Sisko stares at the Saratoga as it explodes behind them.

Three years later, Commander Sisko finds his son on a holodeck. They are en route to new posting on Deep Space Nine, a space station orbiting the planet Bajor, recently liberated after decades of military occupation by the Cardassians.

Three years later, Commander Sisko finds his son on a holodeck. They are en route to new posting on Deep Space Nine, a space station orbiting the planet Bajor, recently liberated after decades of military occupation by the Cardassians.

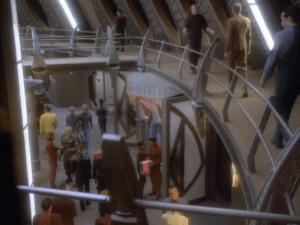

Sisko arrives at DS9 and finds it a mess. Apparently, the Cardassians decided to trash the place during the withdrawal. He is briefed on the station’s status and given a tour by Chief of Operations Miles O’Brien, who along with several other officers, is transferring over from the Enterprise. On reaching Ops, Sisko makes his way into the office and introduces himself to Major Kira, his first officer and attaché to the Bajoran government. Kira is none too thrilled that with the job, as no sooner have the Cardassians been driven off Bajor than the provisional government invited the Federation in. They’re interrupted by news of a burglary on the promenade. Sisko and Kira head down to assist, though Security Chief Odo clearly has matters well in hand. One of the burglars is Nog, the nephew of Quark, the station’s Ferengi bartender and casino operator. Despite Quark’s objections, Sisko has the boy arrested.

On board the Enterprise, Sisko is briefed on the humanitarian situation on Bajor by Captain Picard. Back on the station, Sisko uses the prospect of Nog’s release to blackmail Quark into staying on the station for the sake of economic and community stability. While he is assisting with the cleanup effort, Sisko is approached by a monk who invites him to Bajor to meet with Kai Opaka, the planet’s spiritual leader. Opaka shows Sisko an Orb, an artifact that allows the Bajorans to contact the Prophets, their gods. Looking into the Orb, Sisko relived the day he met his wife. As the Commander recovers from this experience, Opaka explains the history of the orbs and tells Sisko that she believes he is the Emissary, destined to find the Prophet’s Celestial Temple. Though he is unconvinced, Sisko doesn’t dismiss Opaka out of hand, as she will be key to keeping Bajor united.

Back on the station, things are turning around. Quark has reopened his bar and the promenade is coming back to life. Later, the station’s science and medical officers (Jadzia Dax and Julian Bashir) arrive. While Sisko immediately puts Dax to work studying the Orb that Opaka allowed him to bring back to the station, Bashir wastes no time in running his mouth and earning Kira’s ire.

Back on the station, things are turning around. Quark has reopened his bar and the promenade is coming back to life. Later, the station’s science and medical officers (Jadzia Dax and Julian Bashir) arrive. While Sisko immediately puts Dax to work studying the Orb that Opaka allowed him to bring back to the station, Bashir wastes no time in running his mouth and earning Kira’s ire.

As the Enterprise prepares to leave, O’Brien bids farewell to his home for the last six years. Once the Galaxy-class starship departs, a Cardassian warship arrives. Dukat, the Cardassian commander (and former prefect of Bajor) is perfectly civil but leaves no doubt that he’s there to make a point about the station’s isolation and vulnerability. Later, Dax reports that her analysis has given them a place to start their search for the Celestial Temple. But first, they need to sneak past the Cardassians. Taking advantage of Odo’s ability to shapeshift, they are able to blind the Cardassians’ sensors long enough to send a runabout to the Denorios Belt – a charged plasma field where countless strange phenomena have been recorded over the millennia.

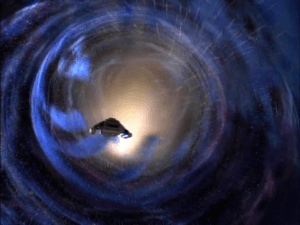

While Sisko and Dax explore the Denorios Belt, their runabout disappears from the station’s sensors. The two soon find that they have passed through a wormhole that has deposited them on the other side of the galaxy. They soon deduce that the wormhole is stable, making it quite unique. On the way back to the Bajoran side of the wormhole, they somehow land on what appears to be an M-class planet, though Sisko and Dax both experience it in different ways (an idyllic park or a barren, stormy rockface) that reflect their emotional states. They are approached and scanned by an object resembling an Orb, which returns Dax to the station as the “rockface” dissolves, leaving Sisko in a white void. Within the void, Sisko begins to communicate with the aliens who live in the wormhole. This is easier said than done, though, as the wormhole aliens are incorporeal and have no concept of linear time.

Back on the station, O’Brien and Dax devise a plan to move the station – under its own power – to the mouth of the wormhole. This is in response to Kira’s need to solidify Bajor’s claim to the wormhole (and, perhaps more importantly, to prevent the Cardassians from staking a claim). As the Enterprise is still the closest starship, they are asked to return to the station, but the Deep Space Nine crew are on their own in the meantime.

Back on the station, O’Brien and Dax devise a plan to move the station – under its own power – to the mouth of the wormhole. This is in response to Kira’s need to solidify Bajor’s claim to the wormhole (and, perhaps more importantly, to prevent the Cardassians from staking a claim). As the Enterprise is still the closest starship, they are asked to return to the station, but the Deep Space Nine crew are on their own in the meantime.

Kira, Bashir, and Odo take a runabout ahead of the station to the wormhole, racing against time and Dukat’s ship. Though they warn Dukat against entering the wormhole, he does so anyway, though the entrance apparently collapses behind him. Meanwhile, the aliens explain, after a fashion, that their existence is disrupted when corporeal beings enter the wormhole and accuse them having no understanding of the consequences of their actions. Sisko explains the nature of experience to them as best he is able, using a game of baseball as a metaphor for linear existence. Throughout this conversation, they continually show Sisko images of the Saratoga, asking why he “exists here.” Eventually, it becomes clear that this refers to Sisko’s struggles with moving on after his wife’s death.

The station makes it to the wormhole, though just barely. Soon after, a group of Cardassian warships under the command of Gul Jasad arrives. Tensions escalate as Jasad jams their communications and demands their surrender. Kira buys time to shore up their defenses and is able to bluff Jasad regarding the strength of the station’s armaments. Unconvinced, the Cardassians attack. Despite a valiant effort, Deep Space Nine is clearly outmatched. But just as Kira is about to surrender, the wormhole reopens and Sisko’s runabout emerges with Dukat’s ship in tow. The Cardassians stand down immediately.

In the aftermath, we learn that the aliens agreed to allow safe passage through the wormhole, and the Cardassians turned tail the moment the Enterprise returned. In a second meeting, this time in Sisko’s office, Picard notes that the wormhole will inevitably boost the strategic and commercial importance of the entire sector and wishes the Commander luck. As the episode comes to a close, we see the promenade, once again a bustling hub of activity.

In the aftermath, we learn that the aliens agreed to allow safe passage through the wormhole, and the Cardassians turned tail the moment the Enterprise returned. In a second meeting, this time in Sisko’s office, Picard notes that the wormhole will inevitably boost the strategic and commercial importance of the entire sector and wishes the Commander luck. As the episode comes to a close, we see the promenade, once again a bustling hub of activity.

Coming into ‘Emissary’ for the first time, the first thing you’ll notice is the pacing. That is to say, it’s much slower and more deliberately paced than any of the ‘Trek’ pilots we’ve covered so far (yes, even ‘The Cage’, notoriously “cerebral” as it is). That’s not to say it’s dull, though. There’s a lot going on here. Though it doesn’t really get moving until the Enterprise leaves and the investigation into the Orbs begins in earnest, that first part of the episode is still packed with character work.

That’s really the key to the whole affair: characters. And that’s what ‘Deep Space Nine’ was interested in, arguably more so than any ‘Star Trek’ series before or since. That is both the greatest strength and greatest weakness of ‘Emissary’. The episode spends the bulk of its runtime letting the audience get to know the cast. That’s a good thing, but it does give the more action oriented elements (such as the almost battle with the Cardassians near the end) a surprisingly perfunctory feel. Though to be fair, it also opens on a spectacular flashback involving the Borg. So there’s that. To be clear, it’s not a bad episode by any means, but this is not yet a show that has mastered the act of balancing character and action.

It’s telling, in fact, that my favorite moments in the episode are all driven more by the characters and their interactions than they are by action. Whether it’s Kira chewing out Bashir, Sisko’s wonderfully tense first meeting with Picard, or O’Brien implementing a little “percussive maintenance” on the transporter, they are all small, human moments, with nary a phaser to be found.

Even beyond the characters themselves, it’s striking just how important the ideas and events that are introduced here will be for the remainder of the series. The Orbs and the Prophets, Sisko’s role as Emissary, the stability (or lack thereof) of the Bajoran government, tensions with the Cardassians, the Kai (though not always this Kai), and more. It’s all right here. But true to form for a show so concerned with its characters, the most important of these to the series identity is the relationship between Ben and Jake Sisko. ‘Star Trek’ had never featured a father/son relationship like that before, and I don’t know that they’d be able to match it if they tried. That relationship more than any other, is the heart of the series, in every sense of the word.

Even beyond the characters themselves, it’s striking just how important the ideas and events that are introduced here will be for the remainder of the series. The Orbs and the Prophets, Sisko’s role as Emissary, the stability (or lack thereof) of the Bajoran government, tensions with the Cardassians, the Kai (though not always this Kai), and more. It’s all right here. But true to form for a show so concerned with its characters, the most important of these to the series identity is the relationship between Ben and Jake Sisko. ‘Star Trek’ had never featured a father/son relationship like that before, and I don’t know that they’d be able to match it if they tried. That relationship more than any other, is the heart of the series, in every sense of the word.

Also of note is the way the show managed to introduce interpersonal conflict into ‘Star Trek’ without invalidating Roddenberry’s humanist utopia. It’s so simple in retrospect, but it’s a code the writers of ‘The Next Generation’ had long been trying to crack. They simply introduced a scenario where much of the crew wasn’t actually made up of Starfleet officers, but rather members of the Bajoran Militia. The clash between organizations, to say nothing of the contrast between the lived experience of twenty-fourth century humans and the living hell the Bajorans had endured during the occupation is practically a recipe for exactly the sort of thing Roddenberry had barred his Federation crews from dealing with. And that’s without even mentioning Quark, who is as much an unrepentant scoundrel as he is “community leader”.

I could go on, but for the sake of hitting my deadlines, I have to draw the line somewhere. Suffice it to say, that while ‘Deep Space Nine’ would, like every ‘Trek’ spin-off, have a shaky first season, they started off on much firmer ground. And more importantly, they would go on to build great things on that ground.

Thank you once again for joining us. As always, I invite you to share your thoughts on ‘Emissary’ in the comments. And of course, make sure you join us next week as we take our first look at ‘Star Trek: Voyager’ with our coverage of ‘Caretaker’.