Welcome as always to the latest ‘Final Frontier Friday’! This week we’re kicking off our countdown to the premiere of ‘Star Trek: Discovery‘. In celebration of both the new series and the franchise’s legacy, every week from now until the end of September we’ll be here covering a different ‘Star Trek’ pilot episode. And what better way to get under way than to look back at where it all began? That’s right, we’re starting with the original ‘Star Trek’ pilot, ‘The Cage’.

‘The Cage’ was developed in tandem with ‘Star Trek’ itself over the course of 1964, which filming taking place near the end of the year. The story was selected from a handful of options following the series’ initial pitch to NBC, at least in part on the basis that the network believed it would be the most difficult to realize and didn’t want to make it easy for Desilu Studios or the production staff to prove the show’s feasibility. This refusal to make matters easy for ‘Star Trek’ would prove prophetic to say the least, even more so than Desilu president Oscar Katz’s concern that the chosen approach would not only be expensive but potentially unrepresentative of the series.

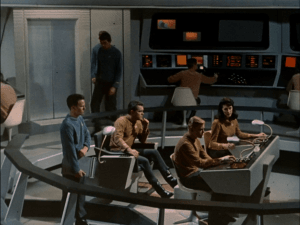

In the earliest drafts of the story, we followed Captain Robert April of the SS Yorktown through an encounter with the “crab-creatures” of Sirius IV (who were later developed into the more humanoid Talosians). As the story evolved through the revision process, it took on a more familiar shape. The Yorktown became the Enterprise, and Robert April was reimagined as Christopher Pike with Jeffrey Hunter cast in the role. But perhaps more importantly, a supporting cast had started to take shape. This included Majel Barrett as Number One (who, according to the actress, was the first character Roddenberry developed after April/Pike), John Hoyt as Dr. Phillip Boyce, Peter Duryea as Jose Tyler, Laurel Goodwin as Yeoman Colt, and of course, Leonard Nimoy as the “satanic” alien Spock. Of the assembled cast, only Nimoy and Barrett would return for the series proper, and only Nimoy would continue in the same role.

Ultimately, of course, NBC rejected ‘The Cage’. The network famously dismissed the episode as “too cerebral”. They also had concerns about the characters of Spock and Number One, with the most common version of the story holding that they worried that one was too alien and the other too female. However, according to producers Herb Solow and Robert Justman, the network’s problems with Number One had less to do with the character than they did with Majel Barrett herself. But while these and other network nitpicks with ‘The Cage’ are often held up as early examples of NBC not “getting” the series (and to be sure, there is a measure of truth to that), we can’t ignore the fact that Gene Roddenberry sold ‘Star Trek’ on the back of one of the most famous elevator pitches in the history of American television: “‘Wagon Train’ to the stars”. In other words, the show he sold was something more akin to a high octane space western than the intellectual sci-fi affair that he actually delivered.

In any case, despite the apparent failure of ‘The Cage’, the story doesn’t end here. Instead, NBC took the nigh-unprecedented step of ordering a second pilot episode. The legend has long persisted among ‘Trek’ fandom that this was a result of Lucille Ball herself championing the show, but Solow and Justman have similarly debunked that one, expressing doubt that she even bothered to read either of the pilot scripts. Instead, it’s likely that the decision stemmed at least in part from the sheer amount of money the network had already pumped into the project. But that’s for another day…

The Enterprise intercepts a fragment of a distress call from the survey vessel Columbia. Absent a stronger indication that there are any survivors (as the ship was lost twenty years ago), Captain Pike is reticent to investigate, especially as the crew is still licking their wounds in the aftermath of a disastrous mission to Rigel VII, in which several crewmen were killed. Privately, Pike reveals to Dr. Boyce that he is burned out to the point of consideration handing in his resignation. The doctor offers him a pep talk (and a martini), after which Spock calls from the bridge, reporting that they have received confirmation of crash survivors. With that in hand, Pike orders the ship to the source of the distress signal: the planet Talos IV.

The Enterprise intercepts a fragment of a distress call from the survey vessel Columbia. Absent a stronger indication that there are any survivors (as the ship was lost twenty years ago), Captain Pike is reticent to investigate, especially as the crew is still licking their wounds in the aftermath of a disastrous mission to Rigel VII, in which several crewmen were killed. Privately, Pike reveals to Dr. Boyce that he is burned out to the point of consideration handing in his resignation. The doctor offers him a pep talk (and a martini), after which Spock calls from the bridge, reporting that they have received confirmation of crash survivors. With that in hand, Pike orders the ship to the source of the distress signal: the planet Talos IV.

On arrival, Pike beams down with a landing party and begins to explore the surface. Before long, they find an encampment of survivors from the Columbia, a group of older men and a young woman named Vina. Despite being a bit disheveled, everyone present looks too good to have been struggling to survive on an alien planet for two decades. Vina takes Pike aside to show him the secret. She leads Pike up an outcropping of rocks before suddenly vanishing. As she does so, a group of aliens emerges from a hidden door, knocks out Pike and takes him captive. At the same time, the survivors vanish and the landing party chases after their captain, though they arrive too late.

Pike awakens in a cell, one of many that he can see. Each cell contains creatures from worlds untold. He is soon greeted by a group of Talosians, including the keeper of this menagerie. From them, he learns that the message and survivors were an illusion, meant to lure his ship to Talos. As Pike begins to realize the extent of his captors’ mental powers, the Keeper remarks on how promising a specimen he is, adding that their experiment can begin soon. Meanwhile, the crew begins to piece together what has happened and just what they’re up against.

While in captivity on Talos, Pike is subjected to a variety of illusions playing off his fears and desires, each designed to bring him closer to Vina (who experiences these illusions alongside him). This begins with a re-enactment of sorts of the mission to Rigel and continues through an idyllic picnic on Earth and a fantasy of life as a trader in the Orion colonies. Through all of this, Pike learns more about the nature of the Talosians and their illusions, including their limitations. Chief among this knowledge is that the Talosians developed their mental powers following a planetary catastrophe and now need him both to live vicariously through his illusions and to breed a race of slaves to rebuild their society. Crucially, their ability to read Pike’s mind (and by extent the efficacy of their illusions) is limited by an inability to break through primitive emotions like hate. This enables Pike to resist his captors, even as Vina tries to convince him (apparently speaking from experience) that this is futile.

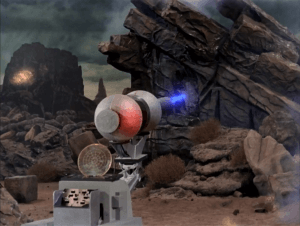

Back on the Enterprise, the crew makes several rescue attempts, including turning one of the ship’s laser cannons on the entrance to the Talosian facility. When this fails, they make a last ditch effort by beaming a rescue party into the compound. The Talosians, however, thwart even this. Demonstrating their ability to use the power of illusion to manipulate the crew into operating whichever controls suit them, the Talosians ensure that only the female members of the landing party – namely Number One and Yeoman Colt – are transported down, and even then, they find themselves materializing inside Pike’s cell. The Keeper explains that since Pike has been resistant to Vina’s overtures, they are offering him a variety of potential mates.

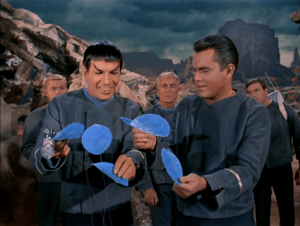

Later that night, the Keeper enters the cell to retrieve Colt and Number One’s equipment. Pike is able to overpower their captor and coerces them into revealing a hole he had managed to blast in the wall using the laser pistols (a hole that had been masked with an illusion). Now free, the Starfleet officers return to the surface with Vina and the Keeper in tow. Once there, the Keeper reveals that this is exactly where the Talosians wanted them to be. As Pike attempts to bargain for the release of his crew, Number One sets her pistol to overload. The Keeper is appalled at the realization that they would rather die than live in captivity. This epiphany is reinforced by data the Talosians have retrieved from the Enterprise’s computer. With this, the Talosians release their human captives and observe that the unsuitability of humans to their needs likely means the eventual extinction of the Talosian race. When Pike suggests a relationship based on trade and mutual cooperation, the Keeper declines, fearing that humanity would learn their power of illusion and destroy itself in turn. As the women return to the ship, Vina insists on staying, as the Talosians reveal to Pike that her youth and beauty are also illusions. With Pike now understanding her desire to stay, the Keeper restores her illusion “and more”, providing Vina an illusory Pike. With that, the captain returns to his ship, the experience having apparently restored his joie de vivre.

As the women return to the ship, Vina insists on staying, as the Talosians reveal to Pike that her youth and beauty are also illusions. With Pike now understanding her desire to stay, the Keeper restores her illusion “and more”, providing Vina an illusory Pike. With that, the captain returns to his ship, the experience having apparently restored his joie de vivre.

One of the most interesting things about ‘The Cage’, especially from a modern perspective, is just how different it is from the show we all know and love, all the while remaining unmistakably ‘Star Trek’. In fact, in a lot of ways, it has more in common with ‘Star Trek: The Next Generation’ than with the original series. Frankly, simply by virtue of the fact that it presents a strong, thoughtful science fiction story, ‘The Cage’ is very much unlike anything else you would have seen on television at the time. Indeed, with much of televised sci-fi still aimed squarely at children and just generally not taken all that seriously, the closest things to that sort of intelligent sci-fi would have to be ‘The Twilight Zone‘ (which, with its O. Henry twists, was more inclined to straddle the line between sci-fi and horror) and early ‘Doctor Who. Indeed, while it’s not a perfect episode, it is a strong first outing. It presents an excellent sense of the sort of show Roddenberry thought ‘Star Trek’ should be, and it’s clear that a fair bit of money was pumped into it, at least by the standards of televised science fiction at the time.

But as I said, it’s hardly perfect. There’s a paucity of action in the episode, and while I would argue it works perfectly fine as a slower, more thoughtful affair, that doesn’t mean it would have gone over well with a mass audience. It does lend some credence (again, especially given its pitch as a western in space) to the network’s concern that it errs a bit too heavily on the side of thinking man’s sci-fi.

Beyond that, the biggest failings here are actually the characters. While I specifically mentioned Majel Barrett earlier, the network wasn’t thrilled with much of the cast, which is underscored by the fact that only Nimoy would return for the second pilot. Though for my money? It’s as much a problem with the script as it is the casting. Hunter, of course, is the notable exception, giving a wonderful performance as Pike. Though as strong as his performance is, the Pike we see here is a world weary, almost broken man. While much of that is likely a result of the Rigel debacle, one can’t help but wonder how much of that characterization would have carried over to the series proper. After all, you can only shift so radically from a character’s introduction, and I just don’t know that a show fronted by the world weary Christopher Pike would have had the same staying power as one headed by the more boisterous Jim Kirk. And honestly? As much as I like Pike, it’s never not struck me as weird that we’re presented with a leading man – a Starfleet Captain, no less – who apparently entertains fantasies of a life as a slave trader. Yeah…

And then there’s the rest of the cast. Boyce is an interesting presence, with shades of what we would later see in a more interesting form with Dr. McCoy. This comes mainly in his relationship with Pike, which provides one of the episode’s most memorable scenes, but also in his brief “I told you so” moment with Number One, which can be read as a precursor to McCoy’s relationship with Spock. Yeoman Colt, on the other hand, is just sort of there, seemingly present first to annoy Pike and then to give him yet another “option” on Talos. Simply put, you could cut her entirely without actually changing the episode in any appreciable way. Astonishingly, Tyler somehow has even less to do. Which brings us to Number One. The character is interesting enough, but to be blunt, Majel Barrett isn’t nearly as good at the “unemotional intellect” act as Leonard Nimoy would soon turn out to be. And speaking of Nimoy, the proto-Spock presented in this episode is a far cry from the character we would come to know throughout the series. That, of course, is because Spock was essentially combined with Number One when that character was eventually scrapped. Because much of his later characterization was originally intended for a completely different character, the Spock of ‘The Cage’ is (like so many others) thinly characterized. He’s basically there as just another crew member, a token alien, as opposed to the signature presence he would later become.

This outing also has a lot – and I mean A LOT – of good ol’ fashioned ’60s sexism. A lot of that comes from Colt, actually, who as I said earlier contributes little more than a pretty face and perhaps the single most unprofessional question ever asked on the bridge of a starship (“Who would have been Eve?”). Even Pike’s first response to her presence, which is to tell Number One of all people that he “can’t get used to having a woman on the bridge” is dripping with it. But lest you think Colt gets all the credit for that, the episode also features Vina, who goes full Stepford wife in the picnic scenario. But that’s nothing compared to the resolution of her arc, which sees her choose to stay on Talos and further has Pike outright say that he agrees with her reasons. Because human society has evolved into a meritocratic utopia that judges people of all races, creeds, and even species by the content of their character, but apparently an ideal society is no place for a sad, ugly woman. Right. Okay. And finally, as entertaining as it is, included is the dialogue between Colt (yes, her again), Number One, and Vina when the former two women first arrive in the Pike’s cell. Suffice it to say, the claws come out. Yes, in spite of the gravity of the situation, you suddenly have all three of these women fighting over a man. Need I say more?

Thanks once again for joining us. As always, I invite you to share your thoughts on ‘The Cage’ in the comments. And of course, make sure you join us next week for our coverage of ‘Where No Man Has Gone Before’, the original series’ second pilot episode.