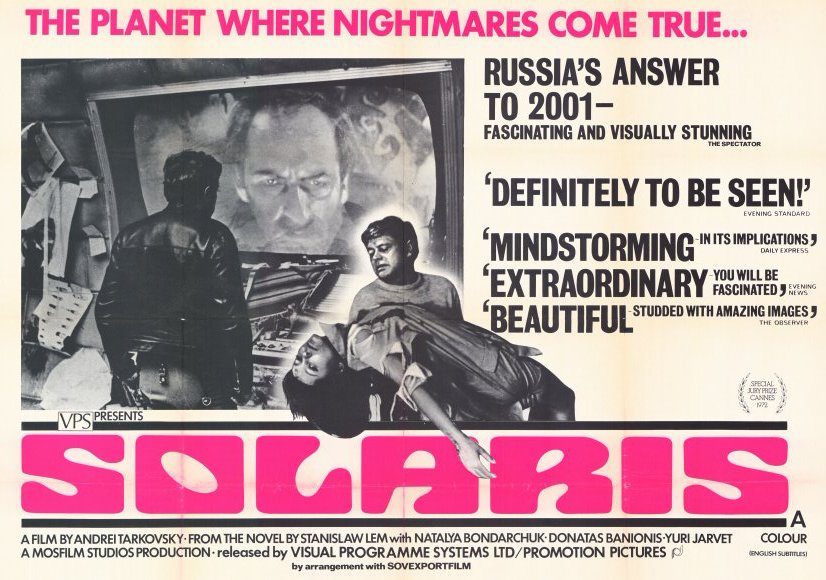

Mention the words “science fiction,” and many minds automatically picture large ships gliding through space, shooting lasers at one another, or bizarre and fascinating alien life making contact for the first time (or invading the Earth). Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky took a decidedly different approach in the early 1970s when adapting Polish author Stanislaw Lem’s science fiction novel Solaris. Tarkovsky’s films contain long sequences, dealing with dreams of metaphysical or spiritual themes, and he put those ideas to use when crafting his vision of man’s exploration of a new world.

In the film, psychologist Kris Kelvin prepares for a journey to a space station surrounding the oceanic planet known as Solaris. Scientists have been studying the watery world for years coming up with a field of study called Solaristics, but strange events concerning some of the scientists have begun to cast doubt upon continuing the studies. One of the space station’s Cosmonauts, Henri Berton, pays a visit to Kelvin before the journey with the hope of helping him understand what he’s about to face.

Berton shows Kelvin a video of a debriefing conference held upon Berton’s return from the Solaris station. During a search for two missing team members who were sent to scout the ocean, Berton’s ship became lost in a thick fog, drawing him close to the water’s surface. In that short space of time, he witnessed peculiar yellow masses flowing up from the water, creating odd shapes – one of which reminded him of an enormous human child, complete with facial features, clothing, and hair. The vision shocked him enough that once back on the station, he refused to leave his quarters or to be in any room with windows overlooking the ocean. The video he recorded during the pass along the ocean showed nothing to corroborate his claims, though.

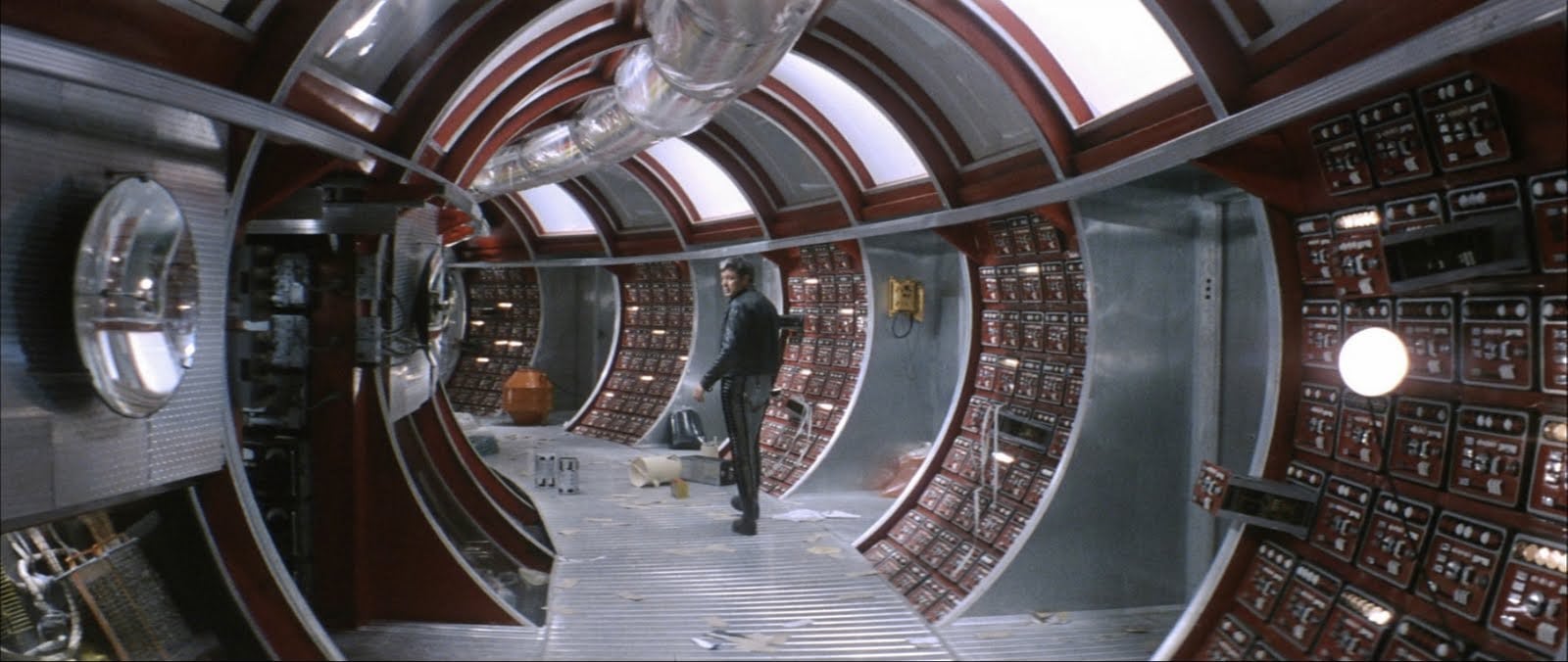

Most of the scientists returned to Earth, but three remained behind, and it’s up to Kelvin to figure out how the planet is affecting the inhabitants of the station. Once he arrives, however, no one is there to greet him. After wandering the long circular corridor, with food containers strewn about the floor and cables ripped and hanging from the walls, he finds the quarters for one of the scientists, a Dr. Snaut. Though Snaut isn’t very communicative, trying as best he can to keep Kelvin from his quarters, Kelvin discovers that Dr. Gibarian – another of the scientists and a friend of Kelvin’s – committed suicide.

Kelvin finds a videotape addressed to him in Gibarian’s room and while watching it, he begins to fall under the influence of Solaris. First, he spies a young woman leaving Gibarina’s quarters, though only Snaut and another scientist, Dr. Sartiorius, are all that’s left of the crew. Then, he encounters his dead wife Hari waiting for him when he wakes in his own quarters. She’s real, flesh and bone, with some memories of her past life. Kelvin immediately devises a plan to get rid of her but learns from Snaut that she will only return. The planet somehow reads dreams and brings to life what each person desires the most.

Snaut goes along with it, not seeing any way to free himself from the inevitable re-birth of a companion each day. Dr. Sartorius, on the other hand, experiments on his companion to determine its makeup and a way to stop them from appearing. Kelvin, not exactly certain of what to make of this solid apparition of Hari, seizes the opportunity to atone for past mistakes with the real Hari by treating this apparition as he should have treated the real thing. As the days pass, Kelvin’s relationship affects that status quo on the space station and Hari discovers how human she has become by making the ultimate sacrifice to save Kelvin.

Definitely not your typical science fiction film, certainly when compared to the galactic-action outer-space films of today. Solaris certainly feels its almost 3-hour length, not because of the pacing of the story, but thanks to Tarkovsky’s signature long, silent sequences that focus on a single object. I’m sure they have something on a very deep level to do with the film, but at first glance, they’re too long and sleep-inducing. When the film reaches the “meat” of the story, though, it’s quite interesting.

Surprisingly enough, the character of Kelvin is somewhat unbelievable. I understand Drs. Snaut and Sartorius actions and motivations after having been stuck on the space station for so long and forced to deal with what Solaris keeps throwing at them. They’ve adapted. Hari (played extremely well by Natalya Bondarchuk) serves as the alien intelligence, trying to understand humans by becoming one of them; she’s innocent and almost childlike as she learns. But Kelvin, after one lone attempt to do something about the strange creature, seems to give up and accept that the creature is his dead wife. And he’s supposed to be a psychologist….

On the surface, Solaris appears to be a story of man making contact with an alien entity, but it goes much deeper in exploring humanity. The three scientists attempt in their own ways to understand the entity as it responds to them with their own repressed fear. But the tables seem to turn on the entity when Hari begins to realize that she isn’t like Kelvin and the others, gaining a human self-consciousness and at the end, acting more human that the three scientists. Very complex and thought provoking.

I don’t mind long, silent sequences as long as they advance the story, or at least, what I believe to be the story. Solaris suffers in that respect, though: an almost 5+ minute scene of a car driving along winding highways and tunnels; a few seconds of a horse; an idyllic slow pan of a lake as Kelvin stares into the water. And I’m not certain if it was simply my copy of the DVD, but scenes changed from color to black & white and back to color without any sense or pattern. But I must give plenty of credit to the production design from Mikhail Romadin. The long circular and disheveled corridors of the space station are some of the best sets on film and assist with providing the somewhat unstable feel of the characters.

Ingmar Bergman considered Tarkovsky to be one of the greatest directors of films. Critics agreed, as four of his films earned the FIPRESCI Prize (from the International Federation of Film Critics) – three of which (including Solaris) were also nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes. The film – and of course, the original novel itself – inspired a 2002 remake starring George Clooney that, sadly, largely underperformed with audiences. As for this version, however, though slow-moving at times to the point of frustration, Solaris overall has incredibly intriguing ideas and themes, and makes for an interesting work of science fiction filmmaking.