Legendary comic book artist Steve Ditko, best known for creating or co-creating a litany of classic superheroes that includes Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, the Creeper, the Question, Squirrel Girl, Hawk and Dove, and such classic villains as the Green Goblin, Doctor Octopus, Mysterio, and countless others has died at the age of ninety. No cause of death has been released at this time, but the New York Police Department has confirmed his passing. Ditko was found dead in his apartment on June 29th, 2018, though he is estimated to have died two days earlier. He has no known survivors and is believed to have never married.

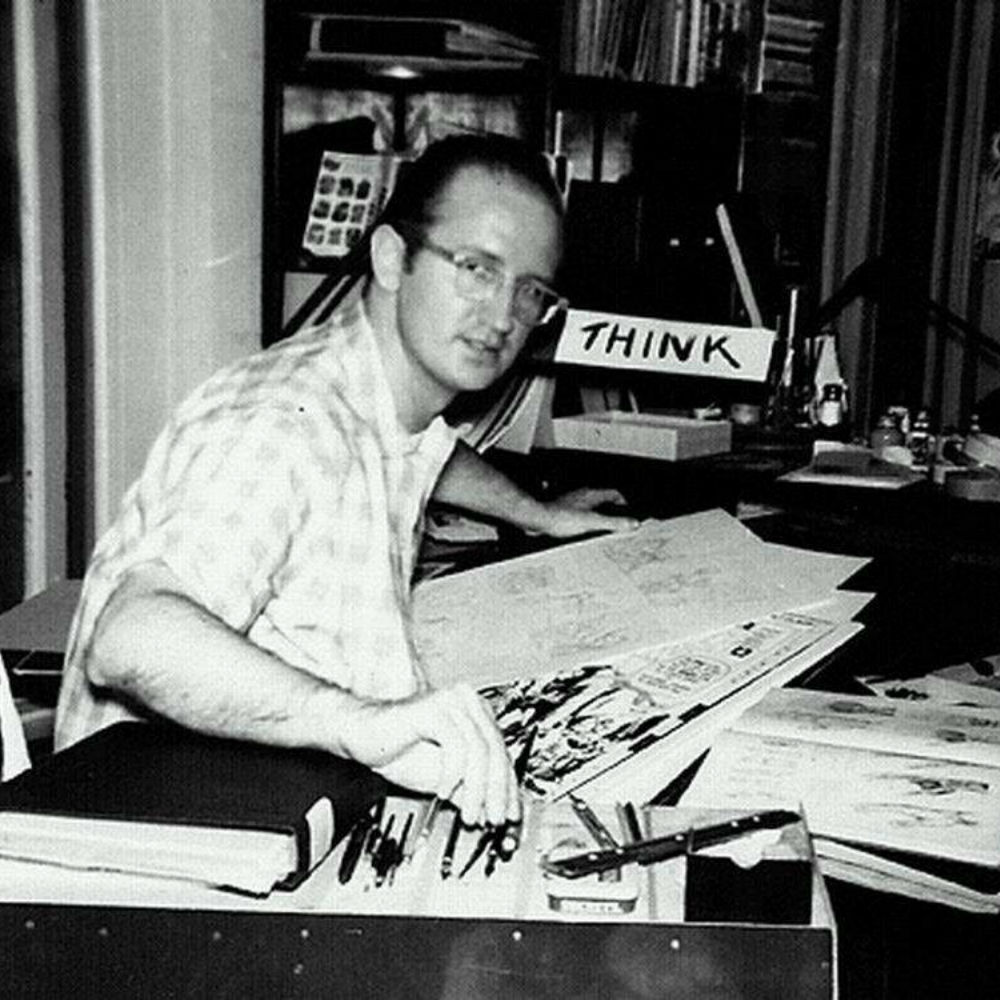

Steve Ditko was born in Johnstown, Pennsylvania in 1927. His interest in cartooning had its roots in his father’s love of ‘Prince Valiant’ strips and the Golden Age comic books (particularly ‘Batman’ and ‘The Spirit’) that were being published during his adolescence. After a stint in the military, during which he served in post-war Germany, Ditko studied under Jerry Robinson (of ‘Batman’ fame) at the Cartoonists and Illustrators School (later the School of Visual Arts) in New York City. By 1953, he was working full time as a comics artist, and in 1955 he began working at Atlas Comics, which would soon change its name to Marvel.

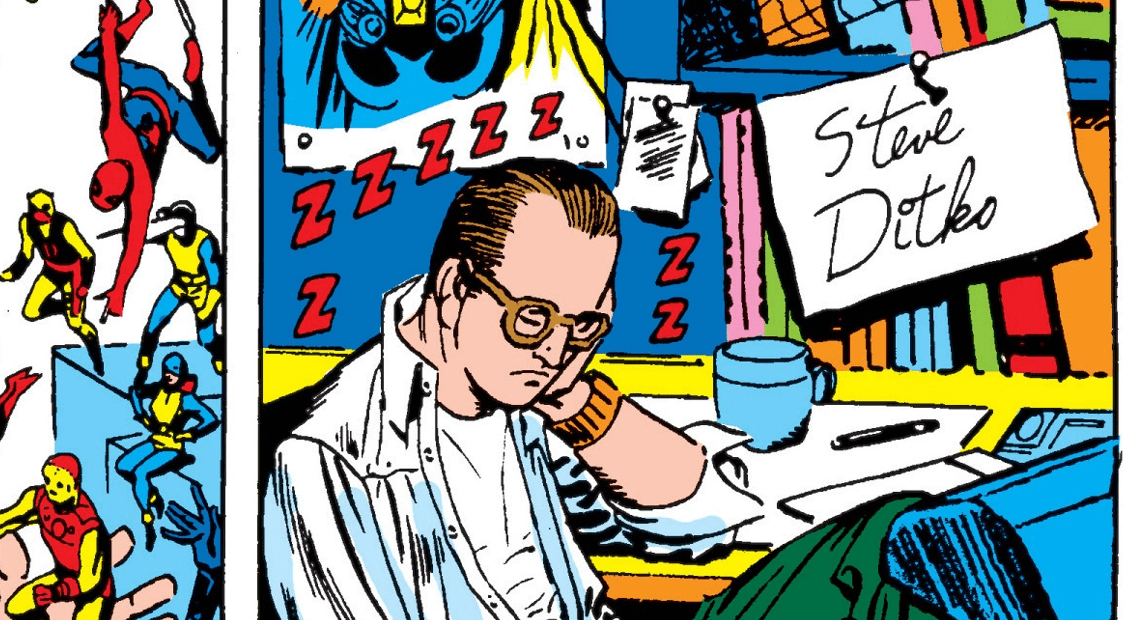

It was during his time at Marvel in the early sixties that he made his greatest contributions to the comic book medium, in the form of his work on ‘The Amazing Spider-Man’ and the Doctor Strange stories he contributed to ‘Strange Tales’. Despite this, he has often been something of an unsung hero of the Silver Age of comics (at least compared to towering figures like Jack Kirby). This is thanks in part to his preference for avoiding publicity. This, in turn, has often led fans and colleagues alike to describe him as the J.D. Salinger of comics, which is to say he was brilliant but also famously reclusive.

It was during his time at Marvel in the early sixties that he made his greatest contributions to the comic book medium, in the form of his work on ‘The Amazing Spider-Man’ and the Doctor Strange stories he contributed to ‘Strange Tales’. Despite this, he has often been something of an unsung hero of the Silver Age of comics (at least compared to towering figures like Jack Kirby). This is thanks in part to his preference for avoiding publicity. This, in turn, has often led fans and colleagues alike to describe him as the J.D. Salinger of comics, which is to say he was brilliant but also famously reclusive.

His influence, though, doesn’t end with the characters he created. He was also a groundbreaking artist in his own right. Ask a panel of comics professionals and they’d likely rank Ditko right alongside Jack Kirby in terms of sheer importance to the medium. To understand why that is, you only have to look at his work. Ditko drew in a distinctive style, instantly recognizable (and often described as “quirky”) for just how outside the box compared to the style of mainstream comics at the time (an aesthetic best defined by the likes of Kirby and Curt Swan).

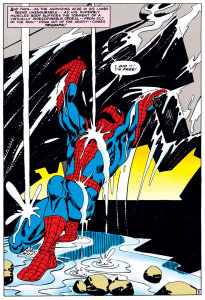

Examples of this can be seen throughout Ditko’s ‘Amazing Spider-Man’ work. For one, there’s his handling of Spider-Man’s physicality. In contrast to the muscular, more conventionally heroic renderings typical of his contemporaries, Ditko frequently drew Peter Parker as a gangly, awkward teenager. As Spider-Man, he would be contorted into all sorts of weird, “spidery” poses. Even the costume design was atypical for a superhero. In fact, it was more like the sort of thing you might expect a villain to wear at the time. And then there are Ditko’s layouts. The opening sequence of ‘Amazing Spider-Man #33’ (the famous sequence in which the wall crawler lifts literally tons of debris off of his back – seemingly through sheer force of will – as the room floods around him and Aunt May’s life hangs in the balance) progresses over five pages from tight, claustrophobic grids into larger, more open panels, culminating in a single, triumphant splash.

And then there’s the sheer out-of-this-world inventiveness of his Doctor Strange work, which is all the more remarkable when you remember that the man never touched psychedelics in his life (though you could certainly be forgiven for thinking otherwise). From the utterly alien interdimensional landscapes to the designs of such esoteric characters as Eternity, the ‘Strange Tales’ stories made clear that Ditko’s was a truly unique visual imagination

And then there’s the sheer out-of-this-world inventiveness of his Doctor Strange work, which is all the more remarkable when you remember that the man never touched psychedelics in his life (though you could certainly be forgiven for thinking otherwise). From the utterly alien interdimensional landscapes to the designs of such esoteric characters as Eternity, the ‘Strange Tales’ stories made clear that Ditko’s was a truly unique visual imagination

And that’s just his Marvel work.

Following his departure from the House of Ideas, Ditko’s work became more explicitly reflective of his personal philosophy. This is especially reflected in characters he developed for Charlton (the Question) and DC (Hawk and Dove), and in his independent, creator-owned character Mr. A. More so than any other, it’s Mr. A that most represented Ditko’s views (and, indeed, often served more as an outlet for expressing exactly that than for traditional storytelling), which were derived from Ayn Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism, particularly its black and white approach to morality. This is often summed up in the phrase “A is A,” meaning that a thing is what it is and can never be otherwise. Or to put it another way, “right is always right, wrong can never be right.” And yes, you guessed it. That is the origin of Mr. A’s name.

Ditko maintained a studio in Manhattan where he continued to produce new material until his death. This later stage of his career was primarily defined by his creator-owned material, though it also saw his pop up in all sorts of unexpected places, contributing to licenses as varied as the WWF and ‘Mighty Morphin Power Rangers’.

Regarding his absence from public life, Ditko (in a rare, late sixties interview) explained it thusly: “When I do a job, it’s not my personality that I’m offering the readers, but my artwork. It’s not what I’m like that counts; it’s what I did and how well it was done.” In other words, Ditko felt that his work should speak for itself. And when all is said and done, it does exactly that.

R.I.P. Steve Ditko: November 2, 1927 – June 27, 2018