And we’re back with another ‘Final Frontier Friday‘! This week we’ll be returning to the second season of ‘Star Trek: The Next Generation’ to take a look at ‘Elementary, Dear Data’. This is the show’s second holodeck episode, after ‘The Big Goodbye’ (though the holodeck itself was used in the interim, it had not been the focus of an episode), and sees the introduction of Data and Geordi’s preference for Sherlock Holmes holodeck programs (though rights issues with the estate of Arthur Conan Doyle would prevent a proper re-visitation for several years). But while that’s an enduring part of both of their characters, it’s not the reason I’m here. That would be Dr. Pulaski. Though this isn’t the first Season Two episode I’ve covered, it is the first time (save for a fleeting appearance in ‘Samaritan Snare’) that I’ve had an opportunity to deal with Dr. Pulaski. And while ‘Elementary, Dear Data’ isn’t her first episode, it does come very much in the phase of the character’s introduction in which her relationships with the rest of the cast were being established.

Depending on which version of the story you believe, Gates McFadden either quit the show (like Denise Crosby before her) or was asked by the producers to leave (due at least in part to the difficulties they had developing her character) at the end of the first season. To this day, those involved tend to play coy with the details, but the more you dig, the more closely the story begins to align with the latter narrative. In either case, with Crusher gone, the show needed a new ship’s Doctor. Enter Katherine Pulaski, a skilled but cantankerous doctor with a distaste for technology. If that sounds familiar, well, let’s just put a pin in that for now. Because I will have more to say later. In the meantime, let’s move on to our overview of the episode itself.

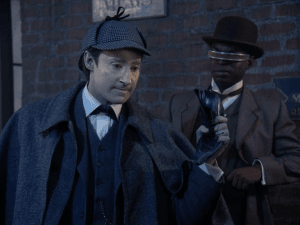

As the Enterprise awaits a rendezvous with the Victory, the crew find themselves with some downtime on their hands. With time to spare, Data and Geordi head to the holodeck, where they assume the roles of Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, respectively. They don’t get off to the most auspicious start, though, as Data’s familiarity with the Holmes canon combined with his android nature means that he goes in already knowing the solution to the mystery. This naturally defeats the purpose. As Geordi explains this to Data, Pulaski insists that while Data is skilled at deduction, he lacks the understanding of the human soul to which she attributes Holmes’s brilliance. Taking this as a challenge, Data invites the doctor to join them.

As the Enterprise awaits a rendezvous with the Victory, the crew find themselves with some downtime on their hands. With time to spare, Data and Geordi head to the holodeck, where they assume the roles of Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, respectively. They don’t get off to the most auspicious start, though, as Data’s familiarity with the Holmes canon combined with his android nature means that he goes in already knowing the solution to the mystery. This naturally defeats the purpose. As Geordi explains this to Data, Pulaski insists that while Data is skilled at deduction, he lacks the understanding of the human soul to which she attributes Holmes’s brilliance. Taking this as a challenge, Data invites the doctor to join them.

After instructing the computer to create a Holmes mystery in the style of Conan Doyle, the trio enters the simulation. The results, though, remain decidedly mixed as the computer essentially presents mashups of different Holmes stories, allowing Data to solve the mystery based on his recognition of plot elements. Apparently vindicated, Pulaski insists that Data’s skills rest entirely on his knowledge of the existing Holmes canon and that he would falter in the face of an original mystery. Unwilling to let the smugly satisfied surgeon have the day, Geordi instructs the computer to “in the Holmesian style, create a mystery to confound Data” and further to “create an adversary capable of defeating Data.” At this, the bridge registers an odd power surge and – unbeknownst to our heroes – Geordi’s use of the interface was witnessed by a character in the program, who remarks that he feels like a new man and summons the holodeck arch before being revealed as Professor Moriarty. Moments later, Pulaski is abducted. Data examines the scene with classic Holmesian deduction, declaring that the game is afoot.

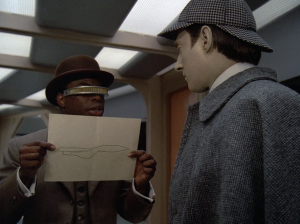

The two follow the trail of Pulaski’s captors, with Data both displaying his deductive skill and demonstrating the scenario’s lack of direct basis in the Holmes canon as they go. They are briefly interrupted by Inspector Lestrade, who summons them to the scene of a murder, which Data quickly solves. Spotting Moriarty in the crowd, the two break away and give chase. Their search takes them through a hidden entrance to Moriarty’s hideout, where the are confronted by the professor. It fast becomes clear that Moriarty knows more than he should, even demonstrating his ability to summon the arch, which a holographic character should not be able to do. Moriarty, genuinely perplexed, asks “Holmes” a number of questions, at one point handing him a paper. With this, Data abruptly leaves, exiting the holodeck and attempting to shut down the system. When he proves unable to do so, he declares that they have to speak with the Captain, handing Geordi the paper, on which we see that Moriarty has drawn an image of the Enterprise.

The two follow the trail of Pulaski’s captors, with Data both displaying his deductive skill and demonstrating the scenario’s lack of direct basis in the Holmes canon as they go. They are briefly interrupted by Inspector Lestrade, who summons them to the scene of a murder, which Data quickly solves. Spotting Moriarty in the crowd, the two break away and give chase. Their search takes them through a hidden entrance to Moriarty’s hideout, where the are confronted by the professor. It fast becomes clear that Moriarty knows more than he should, even demonstrating his ability to summon the arch, which a holographic character should not be able to do. Moriarty, genuinely perplexed, asks “Holmes” a number of questions, at one point handing him a paper. With this, Data abruptly leaves, exiting the holodeck and attempting to shut down the system. When he proves unable to do so, he declares that they have to speak with the Captain, handing Geordi the paper, on which we see that Moriarty has drawn an image of the Enterprise.

As the crew pieces together what has happened, they realize that the instruction to create an opponent capable of defeating Data could perhaps have been worded better, as it unwittingly resulted in the computer creating a sentient hologram – Moriarty. Further, Moriarty has been gradually gaining access to and control of the Enterprise’s systems. Speaking with a still captive Pulaski, Moriarty his growing consciousness demonstrates a desire to leave the holodeck and states that he intends to use her as a lure for Captain Picard.

Picard meanwhile, is already on the way, noting that Moriarty is gaining ever more control of his environment. Arriving in Moriarty’s warehouse, Picard first attempts to defeat Moriarty by giving him what he wants, or rather what he should want. Attempting to satisfy the program’s directive to defeat Data, the Android yields, conceding the “game” to Moriarty. No such luck, as Moriarty’s awareness has only been increasing, allowing him to further exceed his original programming. Using equipment in his lab, he demonstrates an ability to control the ship. He also displays an understanding of his nature as a hologram, though Picard explains that he would be unable to exist outside of the holodeck. As it becomes clear that Moriarty simply wishes to exist and that Picard, in turn, has no wish to kill him, he releases his control of the computer. With Moriarty’s fate in his hands, Picard promises to store his program until such time as a way is found to allow him to leave the holodeck. Satisfied, Moriarty bids his guests adieu before Picard saves and discontinues his program.

Picard meanwhile, is already on the way, noting that Moriarty is gaining ever more control of his environment. Arriving in Moriarty’s warehouse, Picard first attempts to defeat Moriarty by giving him what he wants, or rather what he should want. Attempting to satisfy the program’s directive to defeat Data, the Android yields, conceding the “game” to Moriarty. No such luck, as Moriarty’s awareness has only been increasing, allowing him to further exceed his original programming. Using equipment in his lab, he demonstrates an ability to control the ship. He also displays an understanding of his nature as a hologram, though Picard explains that he would be unable to exist outside of the holodeck. As it becomes clear that Moriarty simply wishes to exist and that Picard, in turn, has no wish to kill him, he releases his control of the computer. With Moriarty’s fate in his hands, Picard promises to store his program until such time as a way is found to allow him to leave the holodeck. Satisfied, Moriarty bids his guests adieu before Picard saves and discontinues his program.

This is a fun episode, and except for some of the discussions surrounding Moriarty at the end, a fairly lightweight one. That’s not a bad thing. I’m a big believer in the idea that when an actor is enjoying him- or herself, it shows in their performance. And the cast is clearly having a ball with this episode, especially Brent Spiner, who is even more of a delight than usual as Data. Really, up until Data’s freak out at the end of act three (when it’s revealed that Moriarty knows more than he should), this is little more than a fun period romp. We still see some of the quirks of early holodeck episodes, in which the characters for whom this technology is a fact of life are as blown away by it as the audience is supposed to be. This sort of thing always leaves me cold. Maybe that’s because I grew up watching ‘Trek’ and as a result take the concept for granted, but it always feels a bit… not “heavy handed” exactly, but like a kid showing off a new toy. “Yes, it’s cool. Can we move on?” Thankfully though, the writers don’t beat us over the head with it the way they would have during the first season, as the gushing is mostly limited to the characters being impressed at the computer’s recreation of Victorian London. And it is impressive. Maybe not BBC impressive, but then the BBC can do Victorian London in their sleep, so it’s hardly a fair comparison. In fact, the episode’s production values are quite impressive, and it owes most of that to what we see in the holodeck scenes. But just because they don’t bang on about how cool the holodeck is doesn’t mean they haven’t found something to needlessly beat the audience over the head with. In this case, it’s the fact that Data doesn’t recognize the scenario from an extant Holmes story. No, really. He totally doesn’t. Seriously. For real.

I also quite like the show’s take on Moriarty. Though there is always an air of menace about him, at the end of the day whatever threat he poses is born more of a sense of desperation than of genuine malice. This combines with the fact that he is driven by a desire to simply exist presents the audience with a remarkably sympathetic portrayal of an iconic villain. Indeed, he largely conducts himself as one might expect a gentleman of the period, offering the captive Pulaski tea and polite conversation, even as he admits to using her as bait. And speaking of Pulaski…

As I alluded to in my introduction, I chose this episode in part because I wanted talk about Pulaski, a character who, frankly, I’ve never been terribly fond of. Before I get into any particular depth, though, I want to be clear about one thing. While I have many problems with Pulaski as a character, I don’t blame any of them on Diana Muldaur. She did a decent (if not spectacular) job with the material she was given. The problem, ultimately, is that the material was lackluster and the character ill-conceived. I sort of talked around this earlier, but in filling the void left by Dr. Crusher, the producers decided to go with a character who was basically a less likeable female version of Dr. McCoy. Unimaginative as that is, it gets worse. You see, they didn’t limit this to her general disposition and transporter phobia. They also tried to reproduce the interplay between Spock and McCoy, here casting Data in the Spock role. Setting aside the fact that (as the last three movies have made painfully clear) duplicating the chemistry between the original series leads is a fool’s errand, one of the reasons that the constant bickering between those two characters worked as well as it did was that there was never any doubt that for all their disagreements, at the end of the day they had a great deal of respect for one another. You never really get that from Pulaski’s interactions with Data. Here, for example, she seems to wear her prejudice on her sleeves (an odd thing to write about a Roddenberry show if ever there was one), referring to Data – right in front of him, no less – as “your artificial friend” when speaking to Geordi. It’s not just insulting to Data, it even manages to feel condescending to La Forge. And no one blinks at it. But this gets to the heart of why the Spock/McCoy banter worked while the Pulaski/Data model falls flat. As I said, Spock and McCoy fought like brothers, and that’s the key to it. You can sit there and insult your brother all day, but if someone else tries it, they’ll have another thing coming. Here, though? Like I said, it lacks the undercurrent of mutual respect. As a result, it feels less like brothers butting heads and more like Pulaski is making fun of the kid who doesn’t realize he’s being picked on. She sees him as something more akin to a tricorder than a person, and that’s just not the sort of thing you want to see week in and week out. Combine that with the fact that she never really seemed to develop much chemistry with the rest of the cast, and it’s not hard to see why she’s become something of a footnote in the show’s history.

As I alluded to in my introduction, I chose this episode in part because I wanted talk about Pulaski, a character who, frankly, I’ve never been terribly fond of. Before I get into any particular depth, though, I want to be clear about one thing. While I have many problems with Pulaski as a character, I don’t blame any of them on Diana Muldaur. She did a decent (if not spectacular) job with the material she was given. The problem, ultimately, is that the material was lackluster and the character ill-conceived. I sort of talked around this earlier, but in filling the void left by Dr. Crusher, the producers decided to go with a character who was basically a less likeable female version of Dr. McCoy. Unimaginative as that is, it gets worse. You see, they didn’t limit this to her general disposition and transporter phobia. They also tried to reproduce the interplay between Spock and McCoy, here casting Data in the Spock role. Setting aside the fact that (as the last three movies have made painfully clear) duplicating the chemistry between the original series leads is a fool’s errand, one of the reasons that the constant bickering between those two characters worked as well as it did was that there was never any doubt that for all their disagreements, at the end of the day they had a great deal of respect for one another. You never really get that from Pulaski’s interactions with Data. Here, for example, she seems to wear her prejudice on her sleeves (an odd thing to write about a Roddenberry show if ever there was one), referring to Data – right in front of him, no less – as “your artificial friend” when speaking to Geordi. It’s not just insulting to Data, it even manages to feel condescending to La Forge. And no one blinks at it. But this gets to the heart of why the Spock/McCoy banter worked while the Pulaski/Data model falls flat. As I said, Spock and McCoy fought like brothers, and that’s the key to it. You can sit there and insult your brother all day, but if someone else tries it, they’ll have another thing coming. Here, though? Like I said, it lacks the undercurrent of mutual respect. As a result, it feels less like brothers butting heads and more like Pulaski is making fun of the kid who doesn’t realize he’s being picked on. She sees him as something more akin to a tricorder than a person, and that’s just not the sort of thing you want to see week in and week out. Combine that with the fact that she never really seemed to develop much chemistry with the rest of the cast, and it’s not hard to see why she’s become something of a footnote in the show’s history.

Did you enjoy ‘Elementary, Dear Data’ or were you too bothered by the fact that none of this would have happened if Pulaski wasn’t compelled to undercut Data at every turn? And speaking of the good doctor, if you have a defense of the character, feel free to drop it in the comments because I’d love to hear it! And as always, be sure to check back for our next installment!